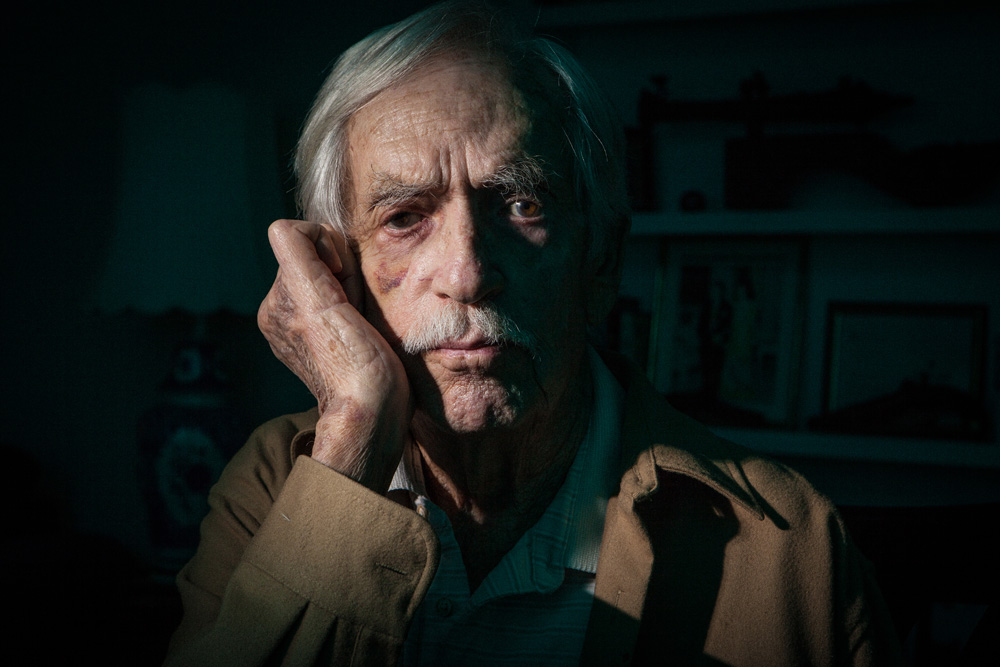

WW II HEROES: Photographs by Zach Coco

Solomon Schwartz

09/15/1918 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Army Air Corps

Solomon Schwartz was twenty-three years old when he enlisted in the Army Air Corps. His unit was shipped to the Philippines that autumn, a place that forever changed him. Little did Solomon know that he was about to become a prisoner of war for forty-two months.

On December 8th, 1941, the Japanese began bombing the Philippine Islands. U.S. troops were ordered to leave the mainland for a place called Bataan, a little peninsula off the coast of the Philippines. Solomon’s unit helped set up a beach defense against the advancing Japanese army, but they were undersupplied and soon forced to concede. “Any American you talk to didn’t want to surrender.”

Solomon was among 60,000-80,000 American and Filipino soldiers who were rounded up by Japanese soldiers and forced to march over sixty miles in what became known as the infamous Bataan Death March. Solomon marched in the scorching sun without food or water. If a prisoner ran out of line to search for something to eat or was thrown food from Filipino civilians hiding in the jungle, they were killed. This pattern continued for days, countless men on the march were bayoneted or shot by the Japanese.

The only water available to drink along the march was contaminated by corpses. Solomon suffered from dysentery by the time he reached Camp O’Donnell, the prisoner of war camp. “I’m not sure how many days it took. It seemed like a lifetime to me.”

At Camp O’Donnell, the Americans and Filipino soldiers were separated into different areas. It was a decrepit old camp whose barracks were falling apart. There was not enough room for all the American prisoners, forcing two-thirds of them to sleep out in the open where it rained relentlessly. There were only two water fountains at the camp for thousands of prisoners. They had to stand in line for hours to get a canteen of water. The camp was so overrun by disease and filth that the Japanese never entered. Instead, they threw food over the fence. Solomon’s health quickly depleted from dysentery.

He wandered around the camp begging for food before collapsing into a slit trench. Two Marines helped pull Solomon out, bathed him, and scrounged food from other prisoners. Yet despite their efforts, his condition only grew worse. He was sent to a barracks for sick inmates, but everyone knew it was the place you went to die. Solomon couldn’t stand watching his comrades die next to him and mustered up enough strength to break out.

Solomon drifted in the camp, cold, naked, and covered in filth. He would crawl under the old barracks to keep out of the rain. He lived like this for four months when one day he found himself slumped on the ground from sickness. Two men were talking above him, one attempting to pick him up. “Let him lay there. He’s going to die,” the first man said. “No, we have orders to take him,” said the other.

They put Solomon on a truck and transferred him to Camp Cabanatuan, a prisoner of war camp where the death rate was sky high. Solomon beat the odds, and, within a few days, he began recuperating from his illness.

The Japanese army then began shipping prisoners to Japan for forced labor. When Solomon thought back to that treacherous journey, he recalled it being as bad, if not worse, than the Bataan Death March. They sailed on old freighters previously used for shipping horses. The two rooms on the ship held 1,000 prisoners and were so crowded that they were forced to sleep on top of each other. The horse manure and filth hadn’t been cleaned up.

Solomon had a canteen of water for the journey which was stolen one night. They weren’t given any water, forcing the prisoners to drink their own urine to stay alive. The trip took longer than they all expected as American dive bombers strafed the ships, not aware that thousands of Americans were aboard. Half of the ships bound for Japan sank on the way over.

When the freighters landed in Japan, the prisoners were loaded onto a train. “We were told if we opened up the windows and tried to escape the whole train would get killed.” They were taken to one of the worst prisoner of war camps in Japan—Fukuoka Camp #17. Solomon endured 12-15-hour days working in the coal mines while living off one handful of rice a day.

One winter night Solomon was spotted after curfew while attempting to bypass the guards. He was dragged into the guardhouse and ordered to take off his clothes. They dumped buckets of freezing water over his head, making him stand for two hours in the cold before locking him in a small wooden cage for a week.

When Solomon was released from the guardhouse, he went back to working long hours in the coal mines, walking two miles barefoot back and forth from the camp. “I didn’t have shoes on my feet for 3 1/2 years.”

On August 9, 1945 Solomon was working in the coal mines when the power suddenly went off. He climbed out of the dark mineshaft, discovering that the shaft had saved his life. He was only twenty miles away from Nagasaki where the atomic bomb had just been dropped.

By September, Solomon was a free man and managed to make the four-hundred-mile trek to an American air base. He had been a prisoner for forty-two months and weighed 81 pounds. Solomon was placed on a ship headed for the States, and, when it arrived, the crew was about to carry him to the dock on a stretcher. He refused. “I wouldn’t let them. I half crawled down.” He kneeled on American soil for the first time in over three years and kissed the ground.

After years of recovery, Solomon made his way back into civilian life. He married his wife, Betty, in 1947 and ran a jewelry shop in Beverly Hills for forty years, casting jewelry for celebrities such as Elvis Presley. When asked what kept him going during those horrific years as POW, Solomon said, “It’s just what you did. I was a prisoner and I didn’t want to die.”

Solomon frequently stated that “you have to live the best life you can.” For him, that meant forgiving the Japanese guards who beat him. Forgiveness gave Solomon freedom to live his best life.