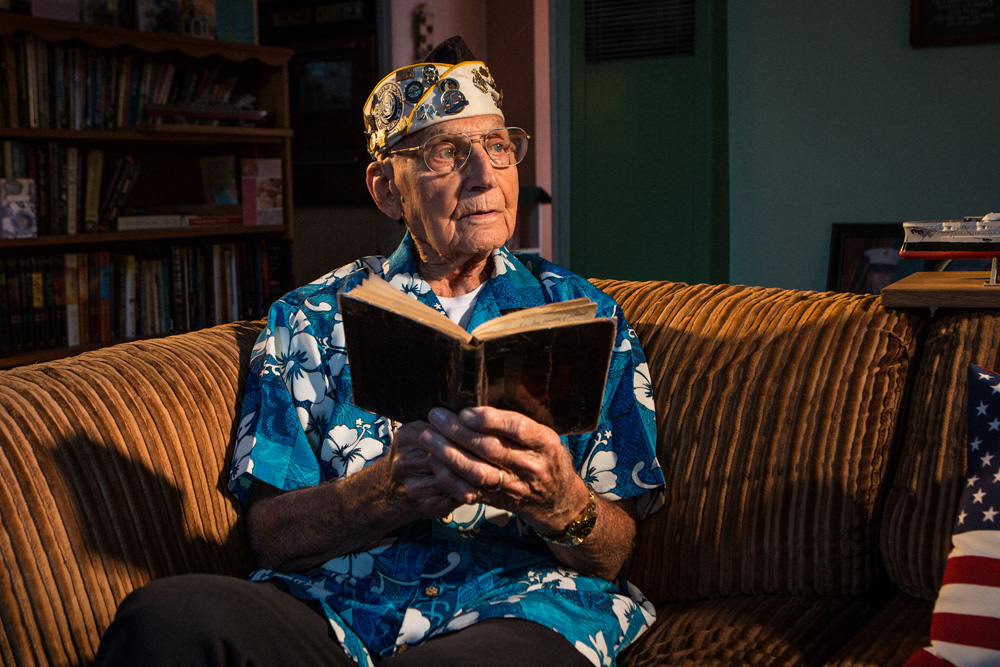

WW II HEROES: Photographs by Zach Coco

Stuart Hedley

10/29/1921 West Palm Beach, FL Navy

Born in Florida, his mother left the family before his first birthday. He and his father then moved to Buffalo, New York where his dad met a woman whom Stuart said, “Her and I didn’t click.” His grandmother raised him until she passed away when he was 9. After he had moved back in with his father and stepmother, his stepmother—who was “insanely jealous”—came at Stuart with a butcher knife, and he knocked her out. It was shortly before what would have been his high school graduation. Although he’d been focused on keeping his grades up in hopes of being accepted into the Naval Academy, he lost interest in most everything after the fight with his stepmother.

Hedley left high school and tried to enlist in the Navy. He told the recruiter he wanted a 20-year contract, but the Naval doctor said he was too small at 4’11”. An officer sent him to work in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to build him up.

While in the CCC, Hedley attended church with a young woman he was interested in. One night in 1939 he walked into church, and his life was physically, mentally, and spiritually changed when he was inspired by a man who’d just been released from Sing Sing prison and testified to the power of Jesus. Stuart committed himself to Christ as his Savior that night.

When he grew to 5’2”, he was finally able to enlist in the Navy. Stuart went aboard the USS West Virginia on October 29, 1940 in Long Beach, California, as a seaman apprentice. He had just turned 19. Not long after they sailed to Pearl Harbor.

The morning of December 7, 1941, Stuart was scheduled to go on a picnic with his girlfriend and her mother. He was chatting with a friend when a fire and rescue party was sounded over the loud speaker. They were ordered to battle stations. En route to his, Hedley saw swarms of Japanese planes; one plane was bearing down so close he could see the pilot and co-pilot, laughing. His LT Commander was crouched down, firing at the planes with his pistol.

Hedley got inside his turret and sat in his position as gun pointer. “We could hear the machine gun bullets hitting the turret, and we felt the thud of a torpedo. My shipmate said ‘Stu, let’s see what’s going on,’ so we took the site cap off the periscope, looked through it and BAM! There went the Arizona.”

Hedley at first thought a bomb had gone down the stack because it looked like the ship broke in two. “But I later learned that a 15-inch armor piercing shell went through the starboard side of the forecastle right at the number 1 handling room. 1,000 pounds of black powder in each handling room. That’s what exploded and set off room 2. That’s why the ship looked like it broke in two. 1,177 men died instantly, and I estimated that 32 bodies went flying through the air.”

“About three to five minutes later, there was an explosion in our turret. One of those armor piercing shells came down on the left gun. Over the left gun is a catapult. On that catapult, we had two planes. We kept the gas tanks filled to maximum in case of emergency. That shell didn’t explode, but it ignited the gas, the gas exploded, burnt one plane to a crisp, and tossed the Admiral’s plane onto the quarterdeck. It was burning when I came out of the turret.”

“We didn’t know it at the time but there were only 11 [instead of the usual 12] men who manned the left gun. All of them were burned beyond recognition.”

Normally, in his gun trainer position, Stuart would have been sitting forward with his feet on a platform as he cranked the gun’s dials. But because he knew they wouldn’t be firing 16” guns in Pearl Harbor, he was sitting back in his seat with his feet underneath him.

“When that explosion took place on the left gun, that hatch came blasting right off and went past my legs, tore my foot pedals right off, went underneath the elevating screw. It picked up my gun mate and I—threw us 8 feet back. He yelled, ‘Stu, let’s get out of here!’”

“When we got up on deck we were at about a 15 degrees list. I thought we were going to capsize. While we were standing there, Ensign Sears was screaming for us to get over on the Tennessee. We had our lines, our cables connected to Tennessee but when we started to roll that’s what held us. Our bilge keel locked under the Tennessee. A group of men were opening watertight compartments to counteract the flooding.”

“We watched the Oklahoma go upside down; it took about 12 minutes for it to capsize. Ensign Sears was screaming at us to straddle the lines and go across to the Tennessee. The first group of men who did got machine gunned as they crawled over the lines. I told Crosslin, ‘We’re not going to go over any lines. And by the way, if I don’t get killed today, I’m going to live to see the end of this war. If you’ve got the faith to believe it, you can do it.’”

While they were watching the Oklahoma go over, Mr. Hedley noticed the 5” guns sticking out over the side of their ship. He told his gun mate they were going to run over the gun barrels to get to the Tennessee. They ran to one of the gun turrets, where a Marine said, “Haven’t you had enough of those turrets? Run, you idiots!” as he pointed to the beach. “How?” Hedley asked, eyeing the flaming pyres between them and shore.

“We went over on the starboard side of the Tennessee. There were all these nice neat piles of clothes of the guys who’d already stripped down and dove in. I told Crosslin, ‘We’ll strip down to our undershorts. Don’t dive, jump! We’ll go together. Go just as deep as you can, we’ll swim deep’ We had to break surface twice before we got to the beach.”

“When we came up, and you thrashed like mad to get that oil and flame away; it was the hottest breath of air I’d ever breathed in my life. We did that twice; we were at the beach. An ambulance picked us up, took us to the dispensary.”

“When we walked into the dispensary, it was a big patio, and on the decking was a great big red cross that could be seen from the air. They examined us to see if we had wounds of any kind, and if we didn’t, they immediately put us to work with those who were wounded.”

“They gave us a tube of Unguentine ointment for burns, a jar of sulfa drug to put in the wounds, and cans of morphine to administer to those who were in dire pain and dying. With those three items we saved lives.”

“While we were doing that, it was about 9:25, and the second wave was coming in. I looked up and saw planes coming in and yelled ‘Duck!’ We went under beds, tables, anything. The glass shattered from the machine gun fire. One of the planes dropped a bomb right in the center and when we looked over the banister after the dust cleared away, you couldn’t see a speck of red [from the red cross].”

Years later, in 2000, while in Pearl Harbor with some of his fellow veteran survivors, they bought nine leis to put out each of the memorials while they prayed for those who had been lost, the survivors, and their families. Mr. Hedley was incensed to discover there was no memorial for the Oklahoma. He dressed down the memorial’s administrator, which kicked in an official response ending in the construction of a beautiful memorial to each of the 429 men who died on the Oklahoma.

On Stuart’s and his wife Wanda’s 25th anniversary, they went to Pearl Harbor where Wanda learned for the first time her husband had been there. While touring Battleship Row, he was overcome by flashbacks of the attack, alarming his wife. “What’s wrong with you?” his wife asked. “I said, ‘Sweetheart, I never told you this, but I was here on December 7, 1941 aboard a battleship that took 9 torpedo hits and 2 bomb hits. One of those bombs came right through the turret that I was in. Killed 11 men. 2 of us walked off.’”

She was shocked, but he hadn’t wanted to worry her about what he’d gone through. Once she knew he’d been involved in the attack, in 1982 he joined the Pearl Harbor Survivors organization, and she joined with him. “She went with me to all the memorial services every 5 years.”

When he reflected on the attack, Hedley described information he’d found years later that in retrospect made it obvious there was going to be one. The Japanese had modified their weapons to be more lethal to ships, for instance arming the torpedoes with double warheads. In addition, there was sufficient information available to support the idea that President Roosevelt had wanted to go to war against Germany and France but kept assuring the American people only if the U.S. was attacked first. So, he downplayed the intelligence that indicated the Japanese were preparing a surprise attack.

Hedley described how FDR believed war would charge up the U.S. economy, which hadn’t fully recovered from the Great Depression even with the various government programs such as the CCC. And Stuart believed his deception took a toll on FDR, who had it on his conscience when he died.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nimitz was put in charge of the Pacific fleet. Amidst all the gloom and dejection, Nimitz pointed out that the Japanese had actually made three significant mistakes.

First, they attacked on Sunday morning when 90% of the crewmen were ashore, thereby keeping the death toll significantly lower than it was. Second, the Japanese got so carried away bombing ships they neglected to bomb the dry docks, so the ships could be repaired locally rather than having to be towed back to the U.S. And finally, they also left intact the fuel storage depots on the island, so there was plenty of fuel for the fleet.

December 20, 1941, the San Francisco left for Wake Island. Several hundred miles out, the scout plane spotted Japanese at Wake and the skipper decided to turn back to Pearl Harbor rather than risk losing more ships.

On Easter Sunday 1942, Mr. Hedley was visiting with a naval electrician, who asked Hedley if he’d ever considered being an electrician. Stuart had been trying for months to become one and was delighted to join the electrical gang on his ship.

Hedley’s close calls didn’t always involve combat. In June 1941, aboard the USS West Virginia at Pearl Harbor, he was told he was being transferred to the USS Houston in the Asiatic Fleet. He didn’t want to go; he wanted to go back to the U.S. because he’d just located his mother after 18 years.

Later that morning during gun drill in the turret, he was told to open the right overhang. His hand went through the pulley, crushing several fingers and cutting off the tip of one. “Johnny Anderson, my buddy, saw the tip of the finger, and threw it to the fish! If he’d brought it down to sick bay, Dr. McCormack could have sewn it back on.” Hedley said.

Because of the accident, his transfer to the Houston was scratched. The sailor who took his place later went down with the ship. “The Lord protected me by the loss of the tip of my finger,” Stuart said. He felt grateful to have never gotten a Purple Heart because during two wars he’d never been wounded.

All told, Hedley and the San Francisco went through 13 major combat engagements. Near Guadalcanal, the ship took seven 14” shells through the bridge. “The thing that saved our ship was the Japanese had all shore bombardment ammo, expecting to bomb the airfield at Guadalcanal, not ships.” Twenty-seven fires were recorded and seven of the eight 5-inch .25 caliber anti-aircraft guns, were destroyed. Stuart was in the only gun that was still operating. All the men operating the seven other guns were killed.

He and Johnny Anderson were close friends, Anderson was a gun pointer. After the night battle at Guadalcanal, Stuart had agreed to identify bodies. He went to gun #5.

“First thing that caught my eye was Johnny Anderson’s upper torso was laying underneath the vent, and his lower torso and legs were dangling where he’d been sitting. That’s where one of those 14” shells came through. The blast tore him right in half.

Well, I started laughing. The doctor doubled up his first and hit me in the jaw as hard as he could swing. He said, ‘Hedley, you have every right to report me because an officer has no authority to strike an enlisted man. But if I hadn’t of done it, you would have gone stark raving mad,’” Stuart recalled.

If Hedley could give a message to his lost shipmates, he’d tell them, “You are the heroes of World War Two. You gave the ultimate sacrifice for the freedom that I, and you, enjoy today.”

When in his 90s, he reflected on the lives of the young people he’s met, he noted, “Today is ten times more dangerous than what I lived in. I tell the kids, ‘Keep your eyes and ears open, and know what’s going on around you. America is asleep. 95% of people don’t care what’s going on.’”

Mr. Hedley was a two-time cancer survivor in addition to being a combat veteran. And he would like to be remembered as a man who trusted his Lord and was thankful for the privilege of serving him all these years.