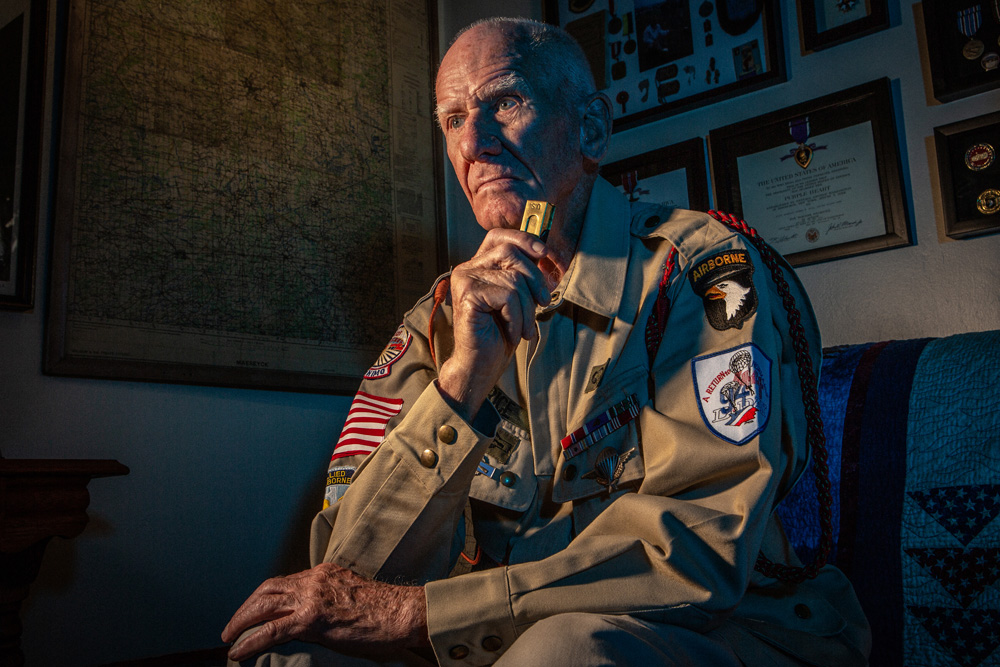

WW II HEROES: Photographs by Zach Coco

Thomas Rice

08/15/1921 Coronado, CA Army

Standing in the door of the C-47 transport plane Thomas Rice was afforded a spectacular view of the light show created by tracers. Flying too high and way too fast, the red light above the door turned green. Shoving a 300-pound bundle of supplies through the door, he was knocked back and down as the slipstream thrust the bundle back in. With another mighty push, the bundle went out and so did Rice, the 1st paratrooper in the transport. Buffeted by the slip stream, he was caught by the arm in the door, half in and half out, flopping in the wind as other paratroopers exited. Freeing himself, he began his descent and watched as the ground came to meet him. It was 0121 hours, June 6, 1944.

Thomas Rice was the older of two children born to Marcus and Catherine Rice. His father was killed in a naval aviation accident, leaving Catherine to raise the two children alone. During the Great Depression, Thomas was able to earn money by “gopher trapping,” receiving a quarter per gopher. In high school, he began running long distance and cross country, continuing as a student at San Diego State. While playing basketball with friends, the news of Pearl Harbor came over the radio, and Rice thought seriously of enlisting.

A natural “risk taker,” he learned of the burgeoning parachute forces and thought it looked “mighty nice.” Rice “went for it” and on November 17, 1942 was on his way to Camp Toccoa, Georgia. Rice fell right into the strict 13-week training regimen of physical conditioning, weapons and tactics training. Those who could not adjust were quietly sent away to complete regular infantry training. The iconic Mount Currahee was a constant presence, and Rice proudly maintained that he beat the time record running the mountain though he kept this quiet while training. After Toccoa, the soldiers went to Fort Benning, Georgia for additional infantry training and Jump School before unit maneuvers and transfer to Europe.

Having reported to the 501st on Thanksgiving Day, 1942, he celebrated New Year’s Day, 1944 in the quarantine ward of a hospital in Glasgow, Scotland suffering from mumps. Combat training continued, though not with the previous intensity. Three practice jumps were made, although the third “jump” was made from the bed of moving trucks! During the first week of June, the 101st Airborne Division moved into marshalling areas and waited. After a false start on June 4, the 18 men of Rice’s stick loaded aboard their C-47 on the 5th, and left England at 2221, English Double Summer Time.

Evasive air maneuvers left thousands of troops scattered throughout the Normandy area. Airborne troops, trained to coalesce into small groups, reorganized on the ground. Soldiers accomplished their missions with whatever group they found themselves in. Rice joined together with one of these groups after discarding most of “the crazy bric-a-brac, death dealing equipment” he no longer needed. Encountering an elderly man, wearing a white, tasseled stocking cap, white night gown and carrying a candle caused Rice to break out in laughter as the resemblance to Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol was simply too much. Leaving the man behind, Rice led several soldiers forward though he did not yet feel the gravity of war. Rolling a live grenade into the ditch alongside that road finally registered that “the war was on from there.”

The men of the 501st fought enemy units, attacked, captured, patrolled and garrisoned road hubs and communications centers. The first day Rice’s unit encountered a German unit whose commander felt it was “too early in the day” to surrender. This was Rice’s first battle. It was on the second night of the invasion that Rice realized “the gurgling sound of a dying man stops all conversation.” There were 35 more nights before he returned to England to prepare for his next combat jump.

In England, replacements were received and integrated into the now veteran units. On September 17, what appeared to be a routine training event suddenly changed, as ammunition was issued for the first time since Normandy.

For Rice, Operation Market Garden began in the wrong place. With no opportunity for mission specific training, his aircraft overflew the drop zone forcing Rice and his men to run 10 km to get to their initial point, the town of Veghal. The paratroopers were surrounded by joyous Dutch citizens as the soldiers desperately tried to set up defensive positions. Soon after, in a classic hammer-and-anvil maneuver, Rice’s battalion trapped a force of Germans rushing to counter the Americans. Rice, a mortar squad leader at the time, fired three rounds at the mass of Germans on the road. Realizing their precarious situation wedged between the forces of an entire airborne battalion, 400 German soldiers promptly surrendered. Rice would spend three months in Holland, returning to France for much needed rest in December 1944.

His rest was interrupted on December 19, by the German Ardennes Offensive. Loading aboard trucks, his unit left for Bastogne at 4 a.m. Despite mind numbing exhaustion and extreme cold, Rice and his fellow soldiers helped defeat this final German offensive. Rice’s participation was short, however, as early in the battle while leading a patrol, he was shot twice by a sniper and evacuated to England.

Rice noted ruefully others received the “luck of the wine and the fraulein” while he was recovering. Reassigned to the regimental track team, Rice placed 2nd in the Third Army 5000m when news of the surrender of Japan arrived. Rather than remain with the Army of Occupation, Rice returned to California to attend college. Always a risk taker, he joined a glider organization for excitement and continued to run marathons until 1990.

Rice returned to Europe several times and made multiple jumps since, in honor of the Anniversary of D-Day. He noted simply that the “wounds have healed, but the scars remain. We did what we had to do.”